By Jack Spiegel

December 14, 2023

The sun sets early these days. And the birds here don’t travel south for the winter. The plants are dormant, and benches, molded from stone, erode as the days and weeks and months and years pass. In the background, the hums of mufflers and muffled hums of cars pass by. Grass grows through the slits at the base of a few traditional wooden benches spotted with bird poop. But it’s not those birds that permanently call the Aurora City and County building home. Those white birds travel in flocks, in and out of the memorial. Thirteen of the 83 total birds have silver-crested wings and are flying in, flying up into the dark blue sky.

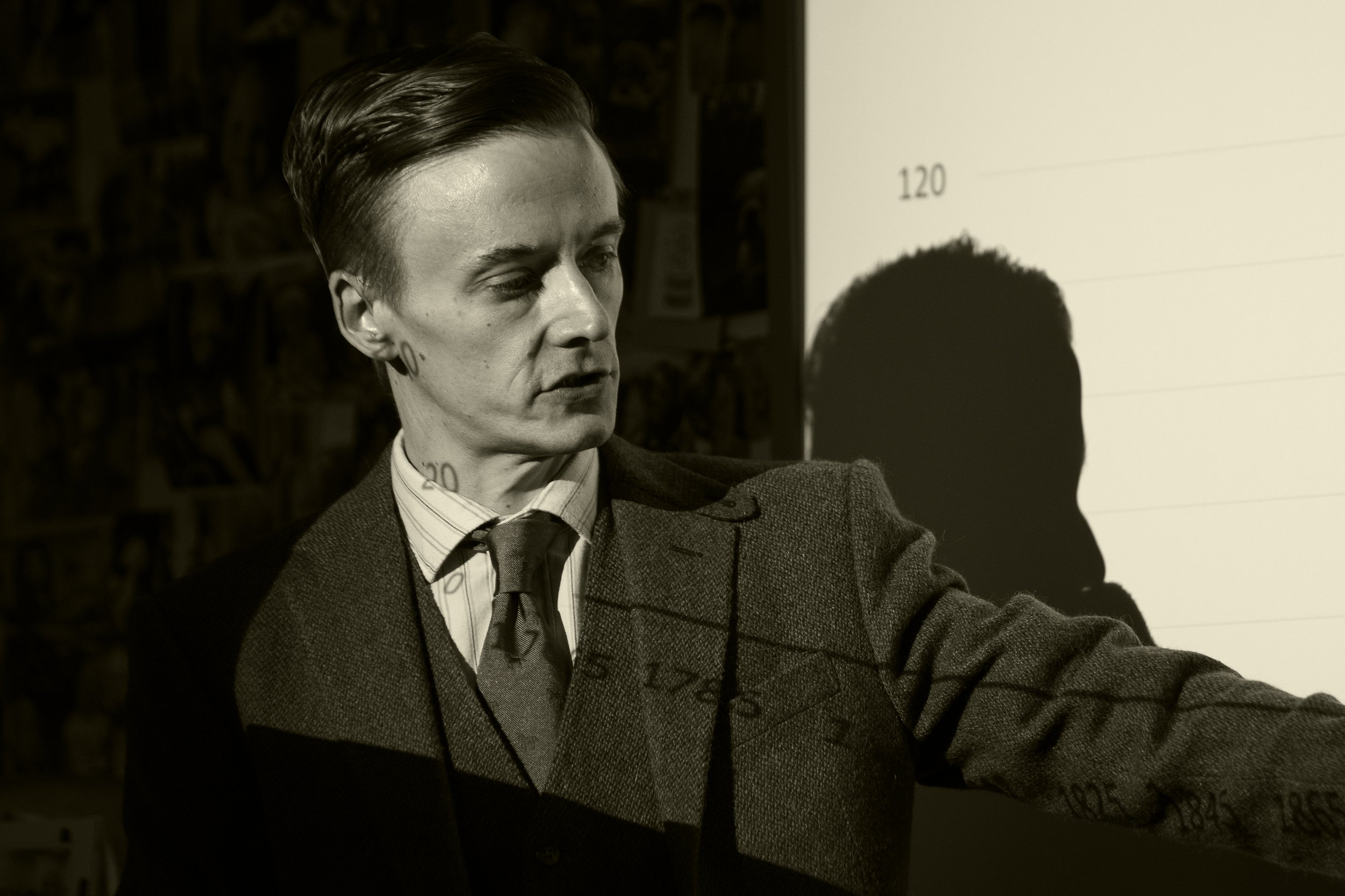

“Asentiate” is the name of the memorial erected at the reflection garden on the grounds of the Aurora, Colorado, Municipal Center in honor of the victims of the Aurora Theater Shooting. 70 pure-white cranes fly towards the center of the memorial symbolizing the 70 people injured as they tried to enjoy their movie. Each crane is hollow and filled with relics from law enforcement who responded that night, and notes of encouragement sent to Aurora after the shooting.

The center of the memorial is 13 translucent cranes with silver-crested wings flying into the sky, repesenting the 13 people who lost their lives in the hours between July 20 and 21, 2012.

In the days after the shooting, hundreds of paper cranes with words of kindness were sent to Aurora from a school in Missouri. Those cranes inspired the work of Douwe Blumberg, the artist who created Asentiate.

Asentiate is made up of 83 total cranes representing the 83 victims of the Aurora Theater Shooting on July 20, 2012. (Jack Spiegel)

Asentiate is a place for unconventional grief to find its own path. In the case of mass shooting survivors, what was supposed to be any other day of the week, turned into the worst day of their lives. It’s not just a place for victims of the theater shooting but rather a place for anyone to reflect.

One person lost their son at the Century 16 movie theater in Aurora, one rushed the injured to nearby hospitals and another spent three hours locked in a bathroom at Columbine High School in 1999.

Each has a different story of grief, and each is now making a difference in their community.

He put his hand up next to his face. Though not wearing a New York Mets’ hat like he is in his official Senate portrait, his white beard still matched his white button-down shirt and white undershirt. When his gesticulations bring his arm next to his face, his half-dozen bracelets move down his forearm.

Tom Sullivan, 67, remembers everything from that July day, the day after his son, Alex’s, 27th birthday. Waking up for his early-morning shift at the post office, making his morning coffee and turning on the TV to check the late-night baseball scores – just like he did every morning for 28 years. The local news was the first thing on the screen, with visuals from a local movie theater that experienced a shooting overnight.

He got in the car, left Alex a voicemail – assuming he was asleep after going to a midnight screening of The Dark Knight Rises– wanting to wish him a happy birthday.

Between the hours of 3:30 a.m. and 6:30 a.m., Tom left a voicemail for Alex every half hour.

On Tom’s first break, he called his wife Terry to see if she heard what happened at the theater and if she had heard from Alex.

She hadn’t heard from Alex because he had been shot and killed.

That was the moment the events of an ordinary day turned Tom and Terry Sullivan’s plans for retirement into plans for a funeral.

Looking back, the start to that July day was anything but ordinary. The TV did not have SportsCenter on, but rather the local news. There weren’t graphics showing how many runs were scored in the Mets’ game, but rather live images from the Century 16 movie theater in Aurora. Tom’s daily commute took him past that movie theater, but instead of it being a quiet, dark morning, blue and red lit up the sky and whirring helicopter blades filled the soundwaves.

“They’re right here off to the side every single day,” Tom said – putting his hand up to the right of his face to signify the memories from July 21. “If you move quickly, you bump right into them.”

Alex was Tom and Terry’s firstborn, and the son that every father asks for. There wasn’t a place Tom could go and not take Alex along. What truly meant the world to Tom was Alex’s ability to get along with people of all ages. His own friends, Tom’s friends, children, his grandparents and aunts and uncles.

Alex had a unique ability to connect with anyone he crossed paths with.

Every year, Tom and Alex would go to a sports trading card convention. When Alex was 8 or 9-years-old, “A League of Their Own” premiered, and they had a booth at the convention with some of the women who played baseball during World War II.

“He was sitting with them – they were like his grandmother,” Tom recalled. “They were selling pictures and T-shirts, and all that kind of stuff, and he would just help them.”

Alex both listened to the stories of the women running the booth, and returned the favor right back to them.

“He just had that ability to – if you were having a bad day or something bothered you, he could tune into it,” Tom said. “Whereas a lot of people might sense it, but don't know how to do anything about it. And I'm not sure that he always knew how to, but he would at least let somebody know ‘I'm here.’”

Each February, Tom would go on a trip to Las Vegas for the Super Bowl with his friends. It was just Tom and his friends until Alex turned 21 and joined the trip.

On the last trip to Las Vegas that Tom and Alex went on together, they were just about ready to go back to their hotel when Alex said that he wanted to stay out longer. Tom took Alex to the Gold Coast casino where they went on a great run.

“We went over to this little bank of machines and played nickel video poker, and we bet between each other who would get a four-of-a-kind kind first or win the dollar,” Tom said. “Every time that I’ve gone back since then, I make a point to go to that area and sit there and play.”

The most recent time Tom went back to the Gold Coast, they were upgrading their facilities. To most, this was a welcome change, but to Tom it was like putting a veneer over his memories with Alex.

“It was kind of sad to walk in and expect to see an old friend, an area that you knew, and then it’s changed,” Tom said

“He was just a great guy to hang out with,” Tom said.

Tom and I spoke 588 Fridays after the shooting. On the one-year anniversary of the shooting, Tom realized it had been 52 Fridays since his son was killed.

“I can see a Friday. I'm not sure that I can always see the next month. I don't know that I can see the next year. But I certainly can see the Friday, and so you do everything you can to get through the week.”

Aurora is a suburb east of Denver with a population of about 400,000. Stretching from the outskirts of downtown to the beginnings of the Eastern Plains, Aurora is home to both economic and social diversity, and a variety of cultures and experiences.

While known for its authentic food scene and beautiful views of the Rocky Mountains, it is a vast juxtaposition from neighboring cities like Cherry Hills Village, Colorado.

Over 90% of residents in Cherry Hills Village are white compared to a mere 55% in Aurora. In Cherry Hills Village, the median household income is $250,000, compared to $72,000 in Aurora.

Those two cities are only separated by 5 miles.

The violent crime rate in Aurora is ten incidents per capita, so shootings there aren’t uncommon.

It was any other graveyard shift for Aurora Police Officer Cody Lanier in the early- morning hours of July 20, 2012. Noise complaints, late-night fights and speeding tickets occupied his night.

When Lanier heard a high-pitched tone and alert from dispatch that there was a shooting at the Century 16 movie theater, no alarm bells went off in his head.

He knew that other units were dispatched to the scene, so he continued to deal with the fight he was breaking up. About 20 seconds later, another alert came through Lanier’s radio stating that there was an active shooter at the theater and there were multiple victims.

The people Lanier was writing up told him that he had “better shit to deal with,” to which he agreed and sped over to the Century.

“At that point in time I felt like nothing I was doing was fast enough,” Lanier said.

The Century 16 movie theater was renamed to the Centruy Aurora and remodeled nearly 6 months after the shooting. (Jack Spiegel)

Lanier pulled up next to another officer on a grassy embankment near the theater. They looked at each other, loaded their rifles and made their way toward the entrance of the theater.

There were reports of gas being deployed inside the theater, but neither Lanier, nor the other officer with him had their gas masks. That didn’t stop them, though.

Before they even made it to the front doors, they ran into a man dragging a heavily injured woman.

“I immediately scooped her up and ran ‘cause I saw an ambulance that pulled into the parking lot,” Lanier recalled. “As we're doing this – the flood of people that was just pouring out of the theater. It was overwhelming.”

Dozens of people flowed out of the theater. They weren’t just fleeing the scene, but rather a majority of them were injured in one way or another. Lanier and his colleagues assessed the severity of those injured, and determined who needed immediate medical attention.

Before he could even finish assessing injuries, an Aurora PD commander flagged Lanier and told him to follow his every move and write down what he saw. How many people are at the scene? Who are those people? What resources does APD have available?

As useless as he felt, Lanier trailed his commander until he heard someone say that they needed a place to bring survivors and witnesses.

A former school resource officer at Gateway High School, Lanier still had keys to the school. He got approval from the school district and began coordinating reunification efforts at Gateway.

Numerous family members went up to an uninformed and powerless Lanier asking about the status of their loved ones in the theater. One particular interaction sticks with Lanier, though.

AJ Boik was likely dead when his mother, Teresa, and fiancé, Lasamoa, found Lanier at Gateway. He was immediately peppered with questions asking: Where’s AJ? Is AJ OK?

Not only did Lanier have no idea where AJ was, he had no idea who AJ was.

After that interaction, Lanier found a victim advocate who had updated hospital lists with the names of survivors. While information was still scarce, AJ’s name was not on that list.

AJ’s mother collapsed when Lanier broke the news to her as he knew it.

“We have an updated hospital list and he is not at a hospital. I don't know what that ultimately means,” Lanier said to Teresa and Lasamoa. “We have a dozen people that are in that theater that are deceased, and at this point in time it appears as if AJ is one of those in the theater.”

After giving both a hug, Lanier returned to his cruiser, defeated. The adrenaline rush was gone.

He remained on duty at Gateway until noon the following day. Just 11 hours and 42 minutes after the shooting began.

A green, three-piece, tweed suit, paired with a pumpkin-pie orange tie patterned with brown horses was the perfect choice for a cold, autumn Monday morning. This carefully thought-out outfit was not a one-off for Fletcher Woolsey.

“To this very day, you could pick anything that I wear on any given day, and I can tell you the historical origins of it, where it came from and who wore it first,” Woolsey said.

For starters, a three-piece tweed suit is very practical. The vest was simply meant to be an extra layer of warmth when central heating did not exist. Tweed is a heavy fabric that was meant to be worn with country clothes. If your pants got caught on a branch while wearing tweed, there was no need to worry about them ripping. His Austrian Alt Wien (old Vienna) brown leather shoes with thick soles were meant to protect your feet against the taxing cobblestone streets of Vienna. His argyle socks are adopted from a specific family’s tartan that pairs well with the country style of his suit. And to bring it all together, his tie is an homage to the Crimean War. Croatian soldiers distinguished their units by wearing different colored scarves. The French stole that idea and eventually created what we know today as neckties. The orange color and horse pattern on the tie would traditionally symbolize your membership to a club, and that is where the term ‘club tie’ originates.

Fletcher Woolsey waits for his students to arrive at his grade-level sociology class at Cherry Creek High School on November 21, 2023. (Jack Spiegel)

Woolsey, 38, teaches sociology, economics and government at Cherry Creek High School in Greenwood Village, Colorado. The bell rings at 9:19 a.m. and Mr. Woolsey tells his sociology class why I was joining them that day.

He left out one key detail: He survived the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School.

As a freshman at Columbine, the cool thing to do during lunch was walk around the soccer field, and young Fletcher was no stranger to frequenting the pitch.

On April 20, 1999, Fletcher’s friends were adamant about going outside for lunch. For reasons still unknown to Woolsey, he refused to go outside that day – a decision that proved to be life-or-death, and one he made before he even knew there was a shooter at his school.

“Two of the people I was with actually ended up getting killed,” Woolsey recalled. “Which, out of 13 victims, the fact that two of them were sitting with me right before they died is a pretty high percentage.”

Those two people he was with were two of the people who tried convincing Fletcher to go for a walk around the soccer field.

For what Woolsey remembers as upwards of three hours, 14-year-old Fletcher hid in the lunch lady’s bathroom with seven or eight other students as two shooters killed 12 students and one teacher.

“It unleashed this remarkable clarity – it’s this part of your mind that you didn't know existed,” Woolsey said about his thoughts while hiding. “What you are going to do is you're going to hide, and then you're going to hide, and you are not going to move, you are not going to move because there are men with guns here. And they have probably already killed people.”

“And you're going to hope that you aren't next. So, sit down, shut up. And let's figure this out,” Woolsey said.

Woolsey’s memory of the day is vivid, but episodic. While he clearly remembers being in the cafeteria, the lunch lady’s bathroom and outside behind a police cruiser, he does not remember how he got from point A to point B.

That group of seven or eight students was one of the few groups who escaped the school on their own – without a police escort. Their escape led them behind a car which Woolsey swears to be a cop car.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph by Rodolfo Gonzalez shows otherwise. In reality, that ‘cop car’ was just – as Woolsey puts it – a “junky, blue, beat-up car.”

Why – to this day – is he so convinced this car was a police cruiser?

“Subconsciously, it's a shield. The police officer is sitting right next to me with a high-powered assault rifle,” Woolsey said. “The five, six, seven, eight of us are behind this car. We are much safer now than we were because we're out of the building. What perfect symbolism that it's a cop car.”

Because of his background in sociology, Woolsey looks for hidden meaning in just about everything. The gaps in his memory have been filled with constructed memories based on what he knows now. Woolsey estimates that about 65% of his memories are actually of what happened that April day and 35% are what he has constructed in his mind since.

By Fletcher’s senior year, school had largely returned to normal – as normal as it could be at the most famous high school in America. And, normal for a senior at Columbine in 2002 was seeing a tour bus driving through the parking lot for tourists to take photos of the school.

“If you were on a tour of San Francisco, and you suddenly got a good view of the Golden Gate, you pull off to the side of the road. Everybody rushes over to that side of the bus, takes their pictures and you leave. That’s what they did,” Woolsey remembered.

As a high school student, Woolsey matured faster than most people around him, and accepted the fact his school was in a fishbowl.

“I would like to think largely because of the shooting. I probably had a pretty strong sense of what I could and couldn't change,” Woolsey said. “Even at 16 or 17 years old, it was obvious that some things are just going to happen to you, and you can't do anything about it.”

Just because he matured faster than most high school students, that’s not to say he didn’t struggle after the shooting. The first year following the shooting was the most difficult for Fletcher.

“I remember distinctly waking up on the 21st and thinking, well, they're coming to get me,” Woolsey said. “The threat has to be out there somewhere. Right? They're coming to get me.”

Twelve years after Alex was killed, Tom is now a state senator representing parts of Aurora in the Colorado legislature. In the middle of a busy December (including a visit to the White House to meet with U.S. President Joe Biden), Tom made time to tell me more about Alex and his life of public service.

Even though his job has changed, he still carries grief with him every day. On his ride into work, Tom reads the news and catches up on what’s going on around the state and country.

“There's a lot of reflective time when you're just sitting there,” Tom said. “I can start to cry for absolutely no reason.”

It is a lot of weight to carry with him every day, and as time has gone on, his perspective on grief has changed.

Tom never had to imagine preparing for his own funeral, much less the funeral of his son. Going to his son’s funeral was the closest thing to going to his own funeral. But through the grief and the anguish, he never contemplated harming himself. He never wanted to put his wife and daughter through the pain he saw them go through after Alex was killed.

As the years go on, anniversaries have become a formality. “They want to put you on a shelf, and bring you down on the day,” Tom said. “Everyone remembers the shooting on an anniversary, and they talk about the memories they have of their wife or husband, son or daughter, friend or complete stranger. “They want to put you back up because having to carry that every day is too much for the vast majority [of people].

What Tom did not understand until after Alex was killed is that there are people who do have to carry that with them every day. Tom thought he understood that because he already experienced the death of his grandparents.

When Tom’s grandmother passed away, they held the viewing in his house. “I was a little kid coming down for breakfast, and my grandmother was lying in a casket at the bottom of the stairs,” Tom recalled. “I thought I understood what that meant, and how it made me feel, and it's nothing [compared to] how it makes you feel when it's your, when it's your own child.”

Life didn’t stop for Officer Lanier after he was released from the scene following four hours of overtime.

“I wasn't off the next night, I had to work again,” Lanier recalled. “It's not like you had the ability to go home and try to come to grips with everything because, who's gonna cover the road?”

The following night Lanier got the break he needed.

There was a fire at an apartment complex near the Century. To Lanier’s relief, there were no injuries or deaths. All he had to do was hold the scene, and he already felt like he was doing more than the previous night.

“I happen to observe this tiny ass little squirrel on the roof of this apartment building, and I’m like, ‘Oh shit! He’s gonna burn up,” Lanier remembered. “I kid you not, man, as the flames are getting bad, the squirrel superman's it off the third floor of this building and lands into a pool”

Lanier recognized how objectively ridiculous this sounds. There are firefighters working to save a burning apartment complex, and right next to them are at least three cops circling around a drowning squirrel.

Frantically, Lanier scrambles to grab the pool scoop and rescues the squirrel out of the pool.

That was the break Lanier needed to be able to move forward. “We helped something, and I needed some kind of a break from reality for a little bit of time,” Lanier said.

As a law enforcement officer and having military experience, Lanier has responded to hundreds of difficult calls. “Just deal with it. Just roll with the punches,” is how he was trained.

Not dismissing the severity of this shooting, Lanier said, “This call in particular, I would say, bothered me less than some other calls that I dealt with in law enforcement.”

“There were suicides. There were dead babies. There were officer involved shootings. You name it,” Lanier said. “The difference with this call was, it was so much so soon.”

It took Lanier months after the Aurora Theater Shooting to realize how much pent-up trauma he experienced.

Lanier doesn’t dream often. After the shooting, he started having nightmares about failing at his job.

“I had dreams that I actually lost, officer-involved shootings where I was injured or I was killed,” Lanier said.

The dreams became so bad that Lanier experienced a 41-hour period where he did not sleep. During that time, some of Lanier’s partners and survivors of the shooting encouraged him to attend an awards ceremony to commend the actions of law enforcement the night of the shooting. Initially he agreed.

That did not last for long. During the ceremony, Lanier found himself in his basement gym. As much as he loves CrossFit, this was an angry workout. Weights flying and music loud, Lanier broke down.

“How do you celebrate a tragedy? And on top of that, I felt like I was a complete loser,” Lanier said. “I help out one female. And then I had to announce that oh, by the way, your son died. And then I had to follow around a command staff member as a scribe. I felt like I hadn't done anything. I felt like a complete failure.”

It took dozens of conversations with survivors, recounting the night for Lanier to understand that his actions that night weren’t a failure. When he began to hear survivors talk about their educational success and career prospects, he found a renewed sense of purpose.

Lanier realized it wasn’t just that one call, it was the dozens of homicides, suicides, domestic assaults that he responded to over his career. All of that stacked on top of each other sent him into a downward spiral. He had to find a healthy outlet to express his feelings.

When Sergeant Cody Lanier is not working, he is 100% off. Cody has two daughters and a wife who are his world. Cody and his wife host a podcast dedicated to helping people find their personal excellence. Cody is made for Colorado: Hiking, fishing and archery are just some of his favorite extracurriculars.

While Cody’s primary outlets are fitness, ice baths and Wim Hof breathing, he does not believe there is a fix-all.

“As long as it's healthy, as long as it's not that pursuit of drugs and alcohol, pursue it,” Lanier said. “You owe it to yourself, and you owe it to your loved ones.”

Fletcher caught a break on April 20, 1999 and he has taken that break and ran with it ever since.

Woolsey joined the Cherry Creek High School faculty immediately after graduating Colorado State University in 2006, officially making him Mr. Woolsey for the first time.

After every lockdown drill, anytime there were talks of active shooters or any time there was a school shooting, the principal would check in on Mr. Woolsey. He was unphased each time.

Woolsey understands that not everyone reacts the same as him. A fellow Columbine survivor who Woolsey stays in touch with has strong emotions triggered even when a fire alarm goes off.

“She was on a college campus recruiting, and the fire alarm went off for what was apparently a very real fire, and they had to lock them in an auditorium for an hour,” Woolsey shared. “She didn't go back to work for seven months because of everything that triggered and everything that brought up.”

Just because Woolsey’s outward facing reactions are not overwhelming, that doesn’t mean he isn’t uncomfortable by news of school shootings.

“I feel my blood run cold,” Woolsey said.

When he sees aerial footage of students running out of school buildings with their hands on the back of their heads, Woolsey feels the same adrenaline rush that he felt on April 20, 1999. He says it’s one thing for any random person to watch that footage and feel scared, but it’s another thing to have experienced it himself. He feels a different type of connection to the students he sees on TV.

While he grew up in a white, middle-class family, Woolsey blames his early life for his lack of forward-facing emotions. His life between the ages of 5 and 15 sucked. He characterized himself as “weird,” “overweight,” and “empathetic.” He said that being empathetic was, “a minus on the playground, especially in the 1980s.”

He has grappled with the idea that the good life he was born into can be so difficult at the same time. Other survivors of Columbine often asked, “Why did this good life have to end so abruptly?” They had their friends, they had their families, they had their church, but did it have to end in high school?

Woolsey doesn’t feel that way.

“For me, I don't know that it ever really started. To put it quite bluntly, this is another shitty thing to deal with,” Woolsey said. “If I made it through elementary school, being called fat and weird, if I made it through middle school getting picked on, getting made fun of, being told I have no friends, here's another thing that I can say, yeah, that really sucks, I didn't deserve it, [but] I can roll with that.”

While Mr. Woolsey does not outwardly talk about his Columbine experience, he does bring a profound sense of understanding into the classroom.

Mr. Woolsey teaches sociology, economics and government at Cherry Creek High School in Greenwood Village, Colo. (Jack Spiegel)

Generalizing, looking back on his time at Columbine, he witnessed “the terrible student from the broken home” and “the straight A student that had everything going for them” be the emotional rock that people relied on. But, he also witnessed “the terrible student from the broken home” go further off the rails after the shooting, and “the straight A student that had everything going for them” fall apart.

“When I do hear people struggling, I try very hard to communicate some of that strength. This is sad, this is terrible. What are you going to do about it?” Woolsey said.

The four years of high school are some of the most formidable of a young-adult’s life. It comes with new experiences, relationships and incredible joys. High school can also bring new, scary feelings for a teenager: Breakups, personal loss and feelings of failure.

When Woolsey walks through the doors to the East Building of Cherry Creek High School, it is not only his objective to teach students about supply and demand. He helps them find a path through the ebbs and flows of life.

“This is the world. This sucks. How do we navigate this world? Because I think it's how I survived,” Woolsey said.